Entrepreneurship in Colombia Part 2 of 2: Analysis of GEDI Factors

by Lateef Mauricio Abro, at George Mason University School of Policy, Government and International Affairs, April 2012

[Download in PDF Format]

In “Institutional Background Paper for Colombia” (Part 1) we introduced the Global Entrepreneurship and Development Index (GEDI) pillars of “nonfear of failure” and “cultural support” as the two pillars that force Colombia to keep one foot in the “entrepreneurial attitudes” GEDI sub-index, thus preventing Colombia from shifting major attention towards the second GEDI sub-index of “entrepreneurial activity.” It is important for Colombia to solve the shortcomings in the two aforementioned pillars in order to allow the economy to evolve from its current position in the “efficiency transformers” cluster towards the “transitional” cluster – the desired end-state being a move into one of the two “innovation” clusters that would indicate a progressively developing/improving economy. In this paper we will analyze Colombia’s activity in relation to the GEDI pillar of “cultural support,” determining the entrepreneurial activities created by this pillar.

The GEDI has calculated Colombia’s “cultural support” pillar to be substandard (index value of 0.32 with 1.00 being the highest possible value) based on the combination of two variables, the “corruption index” institutional variable (index value of 0.21) and the “entrepreneurship career status beliefs” individual variable (index value of 0.82)[1]. This implies that corruption is at levels that are not conducive to the advancement of entrepreneurship and that entrepreneurship may not be highly regarded and/or encouraged as a career choice. The fact that corruption in Colombia extends to the highest rungs of the national government makes matters worse for would-be entrepreneurs, as they could be amendable to paying off rent seekers in exchange for an opportunity to establish a thriving business; however, with the corruption extending into the very institutions that stand to benefit entrepreneurs, the would-be entrepreneur would forecast a bleak future without having deep pockets and broad networks of relationships with institutions and the figures that lead them.

As to the second factor that stands to weaken Colombia’s “cultural support” pillar, entrepreneurship and innovation are highly regarded qualities that have been witnessed in Colombian culture as early as the independence of Colombia from Spain. In the later half of the 19th century the terms of “merchant” and “entrepreneurs” aren’t merely economic/legal abstractions, rather, they suggest a larger social reality that links those actors to the state, and local communities and families; furthermore, these designations are just as much economic as they are non-economic. [2] During this liberated and inspired period businessmen and farmers worked together to industrialize the nation, rapidly accepting and integrating innovations for processing agricultural products like coffee and yucca, and technologies for facilitating efficient mining of natural resources.[3] Thus, the culture of business, and as a result entrepreneurship, is one that is engrained in Colombia’s history; unfortunately, without stretching too far one can perhaps find that Colombians may have “un-learned” these principles, along with other principles that would facilitate the development of an economy, as a result of very violent armed conflict that began at the end of the 19th century with a political war between conservatives and liberals,[4] spiked in the mid-20th century with “La Violencia,”[5] and then again in the 1960s with a nationwide conflict including the national government, armed revolutionaries, paramilitary groups, and narcotraffickers that still carries on to this day.

Analyzing Corruption

In a 2011 research study that surveyed 530 entrepreneurs, Colombia’s Universidad Externado discovered that 13% of contract value (implying government contracts) is earmarked for bribery. Even with minimal knowledge of the government contracting industry, one can understand the detrimental implications of such a large percentage of contract value – the vendor’s profit margin must exceed 13% by several percentage points just to make the contract a feasible pursuit for potential vendors – these conditions certainly dissuade any vendors that are legally (non-corrupt) pursuing a lucrative outcome for their enterprise. [6] In a 2011 article, the Colombian magazine Semana established a good introduction of the main problems contributing to the proliferation and continuation of corruption as a fact of life in Colombia. The article provides the following five reasons for the continued expansion of corruption in Colombia: 1) Weak institutions whose loosely followed regulations are overlooked by corruption-complicit actors and educational institutions that may not be doing enough to stop the “shortcut culture where everything goes” from being passed on to the next generation; 2) Public acceptance without denunciation is rampant as society at large fails to decry corrupt activities, with businessmen, regardless of reluctance, participating in corrupt contracting accepting corruption as a cost of doing business; 3) Lack of protection for witnesses scares off whistleblowers from calling out corrupt activities as death threats, and follow through on death threats, are common; 4) Lack of education as the public at large generally does not understand how to identify corrupt activities, and procurement officials lack adequate training to conduct procurement activities in a manner that avoids corruption; and, 5) Lack of information regarding government procurements that transparently informs the public of competitive solicitations (less than 0.5% of 158 state entities utilized publicly competitive solicitations for procurements), the number of proposals received, and the selected awardees for government contracts[7].

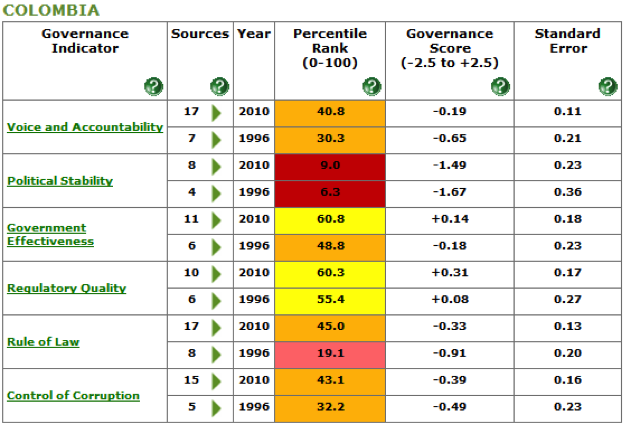

While corruption is recognized as a national problem, corruption has hardly improved over the past decade. The World Bank’s governance indicators for Colombia display a percentile rank increase in their “control of corruption” indicator that is far too small, from 32.2 in 1996 to 43.1 in 2010 (see Figure 1).

There is no doubt that corruption reduces the prevalence and success of entrepreneurial pursuits. The Transparency for Colombia Corporation (Corporacion Transparencia por Colombia), a Transparency International organization, discovered that 84.4% of businessmen stated that they abstained from contracting with the government because competition is unjust, the process is politicized, and kickbacks are commonplace.

| FIGURE 1 |

Worldwide Governance Indicators, World Bank, Accessed 3/9/2012[8] |

Recent Examples of Corruption

A recent audit of 15 Colombian education secretariats discovered $75 million in embezzled funds as school districts created about 100,000 “ghost” students to receive money from the state treasury. Soon after this corruption was made public, some secretariats of the 80 whose audits are pending have deflated their enrollment figures, totaling a reduction of 180,000 students (ghost students) that would equal about $125 million in illegally redirected government funds.[9]

“’This operation (the tax agency) will continue. It’s just one tiny arm of a large octopus.’” These were the words of Colombian president Juan Manuel Santos about an estimated $850 million embezzled from the nation by the national tax and customs agency in early 2011.[10]

In October 2011, citizens of Colombia’s capital city, Bogota, elected a former “leftist rebel” guerrilla to the nation’s “second most important elected office,” mayor of Bogota[11]. A primary reason for his election is his staunch position as an “anti-corruption crusader.” This move to elect a person that was once fighting against the Colombian government is telling of how important the issue of corruption actually is.

The Ends Justify the Means

In a research study that was published in 2010 in the Learning and Management (Pensamiento y Gestión) journal of Colombia’s Universidad del Norte, researchers surveyed 46 entrepreneurs from Bogota to analyze their “beliefs, values and motivations.”[12] Within this research we find that the facts of Colombian corruption do in fact play a role in the Bogotano entrepreneur’s (and as an extension, the Colombian entrepreneur’s) mentality. As one of the surveyed entrepreneurs stated to researchers, “I consider the biggest problem that I have had as my battle against corruption and the lack of ethics.”[13] Furthermore, acceptance and complicity of corruption is reinforced by this research study, indicating that entrepreneurs accept corruption as a fact of life, in the (translated) words of on surveyed entrepreneur, “you have to learn to live with and manage these issues to be successful [as an entrepreneur].”[14] In a 2005 magazine article published by Colombia’s Universidad Central this “fact of life” interpretation of corruption is hit head on by the author as he denounces the hypocrisy of Colombian society’s attitude towards corruption. The author reflects that Colombians view corruption as some foreign pathogen that is purveyed by individual actors, instead of viewing the phenomenon for what it is, a societal problem that has been deeply engrained through decades of accepted proliferation across wide-spreading networks that touch a broad cross section of Colombian society.[15]

Corruption is also augmented by other large national problems such as economic instability, political turmoil, and low enforceability of laws. These issues provide Colombian entrepreneurs with a personal justification for “bending” the rules for the sake of ensuring a good future for their business and local communities. When an entrepreneur under-reports annual earnings to reduce tax liability or pays off a building inspector to overlook a safety flaw, he’s not necessarily the worst “corrupter,” but he is certainly not preventing the continuation of the complacent and self-serving attitude that breeds corruption. In fact, this subjective interpretation of business laws and ethics points at a Colombian entrepreneur that understands the legal way to do business, but is unfortunately operating in an economic environment that is inherently anti-entrepreneurial. Rationally, Colombian entrepreneurs view legal compliance as an important social responsibility associated with operating a business. This is the same type of social responsibility that obliges the entrepreneur to carry the burden of providing a consistent and decent livelihood for their employees, their families, and as a result, their communities at large.[16] This utilitarian consequentialism allows Colombian businessmen to self-justify the selection of good and bad tactics at their leisure – telling us that the psychological and sociological condition of the Colombian entrepreneur deserves pointed institutional attention. There should exist strong and impenetrable institutions to monitor and prevent corruption; however, those anti-corruption institutions must be operated by determined, ethically grounded Colombian citizens. Thus, Colombia must work on improving the cultural aspects that provide oxygen for the blaze of corruption.

Analyzing Entrepreneurship Career Status Beliefs

In a 2011 report published in the International Journal of Business we discover that Colombian university students are quite positive about entrepreneurship in their nation, in fact, the Colombian students often exhibited more favorable to entrepreneurship than students from the other countries in the research sample which included Canada, Tunisia, France, Romania, the United Kingdom, and Germany. More than 25% of the Colombian students considered themselves as born entrepreneurs, followed by 19% of British students. Only 9% of the Colombian students perceived “the lack of profitable opportunities as an obstacle to entrepreneurial development,” while 59% of the German students felt otherwise. Colombian students also led the pack by substantial margins with “93% of them thinking of eventually creating a business” soon after graduation – 63% of the Colombian students claim to have created a business while attending university. Finally, one of the most impressive findings from this research highlights the importance of entrepreneurship in Colombian society as 82% of the Colombian students considered that university courses “developed the entrepreneurial spirit.”[17]

These positive attitudes exhibited by Colombia’s future businessmen and women validate the GEDI’s findings that career status and respect of entrepreneurs in Colombia is at a regionally high 82%.[18] Nevertheless, Colombia’s success in assigning a high career status to entrepreneurs is not enough to convince “the best and brightest” to become entrepreneurs, let alone to develop high impact enterprises. The “high levels of corruption [exhibited in Colombia] can undermine the high status and steady career paths of legitimate entrepreneurs.”[19] If we were to judge Colombia’s ability to produce entrepreneurs that positively impact the nation’s economic development solely using the GEDI’s “cultural support” pillar, the nation’s possibilities would be bleak, primarily due to the high levels of corruption.

Beyond Corruption and Career Status

“Cultural support,” as defined by the GEDI, is a combination of a nation’s corruption index and the career status allocated to entrepreneurs. From the analysis presented above we can conclude that the entrepreneur’s perceived career status in Colombia is at a level that is productive towards the proliferation of entrepreneurship as an attitude; however, we cannot say the same for the corruption index, which is so high that it brings down the nation’s entrepreneur-friendly qualities substantially.

Corruption is the one-eyed monster running rampant through Colombia, conveniently utilized as a form of security for participants and a scapegoat by non-participants, who may be one in the same at different points in time to different audiences. Nevertheless, corruption doesn’t appear randomly from an abyss, it is caused and purveyed by citizens of every nation out of desire or necessity, among other motives. And just as all other nations, Colombia’s economic and social conditions are unique – one key distinguishing factor is the continuous state of nationwide, armed conflict that began in the late 19th century and battles on to this day.

Armed Conflict Impact on the Entrepreneur

The continued state of armed conflict has wreaked economic havoc throughout the nation as the state continues to allocate large portions of the fiscal budget towards the eradication and interdiction of illicit drug trade, and state activities geared towards combatting non-state armed groups. These large expenditures reduce the state’s ability to fund institutions and programs that are fundamental for the improvement of the Colombian citizens’ condition, and as an extension, the citizens’ likelihood of taking on entrepreneurial pursuits. It is difficult to measure how effective each fiscal dollar has been spent on these activities; however, it’s generally accepted that too much money was spent in an uncontrolled, and un-measurable manner. An example is the war against non-state armed groups such as the leftist Armed Revolutionary Forces of Colombia (FARC) and the paramilitary United Self-Defense Forces of Colombia (AUC). In a 2003 paper, author Camilo Azcarate argues that the Colombian government designed and executed flawed peace processes – this helps to validate that money has been mismanaged. Azcarate’s analysis of the failed peace processes identifies the following four critical characteristics of the failed processes, most of which were within the state’s abilities to control: deficient diagnosis, inadequate procedure, preventable manipulation, and unnecessary vulnerability to events away from the table.[20]

The armed conflict has also produced a large number of internally displaced persons (IDPs), “estimated to be between 3.3 million and 4.9 million,” “around 7% of the total population,” with “over half of the displaced” being under the age of 18.[21] These IDPs place additional burden on the localities they migrate to, again draining fiscal funds that could be used to fund entrepreneur-friendly initiatives. Additionally, as migrants, IDPs inherently have a harder time finding employment in their new communities “due to labor market rigidity and the absence of labor legislation conducive to social networks for migrants.”[22]

The preceding examples of the national impact of armed conflict introduce only two broad categories of financial stress for the nation. One would not have to look very far to detect the presence of costly corruption in these two categories; yet, in the same circumstances, one can also detect respect and admiration for the career status of the entrepreneur. Mismanaged, or at least less-than-optimal, government spending becomes even more impotent as rent seekers extract profits from government money through corrupt means – further increasing thoughts of complacency regarding the state’s abilities within the average Colombian’s mentality; thus, reducing the likelihood of entrepreneurial pursuits. In this environment, we reluctantly place the label of “entrepreneur” to rent seekers that bypass social, legal, and ethical norms to develop their own profitable enterprises. Furthermore, these rule-averse business people are difficult to profile as undesirable “necessity entrepreneurs”[23] because it’s difficult to argue for the “necessity” motive when these entrepreneurs begin enterprises that more than meet basic life necessities. These entrepreneurs identify opportunities within a business environment that is rife with corruption, as such, they build their own business codes and relationship networks that facilitate business growth. As their relationship networks grow in size and breadth, these entrepreneurs are able to disguise illicit and/or corrupt activities with increasingly less resistance. This hints at an economy of scale that benefits the expansion of corruption-reliant businesses; thus, these corrupt enterprises become deeply entrenched to a point where corrupt activities are difficult to detect, and worse, once detected the corrupt activities become easier to overlook as rent seeking observers and officials stand to profit from “looking the other way.”

As to the GEDI’s “cultural support” pillar, the entrepreneur’s career status is not a problem in Colombia – the prevalence of corruption certainly is a problem.

ENDNOTES (BIBLIOGRAPHY)

[1] Acs, Zoltan, and Szerb, Laszlo. Global Entrepreneurship and Development Index 2012. Edward Elgar Pub, 2012, p. 119.

[2] Castro, María Fernanda Duque. “Comerciantes y Empresarios De Bucaramanga (1857-1885): Una Aproximación Desde El Neoinstitucionalismo. (Spanish).” Historia Critica, no. 29 (January 2005): 149.

[3] Ibid: 150.

[4] Bergquist, Charles W. Coffee and Conflict in Colombia, 1886-1910. Duke University Press, 1986, p. 103.

[5] Wikipedia contributors. “La Violencia.” Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia. Wikimedia Foundation, Inc., April 12, 2012. http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=La_Violencia&oldid=480310704.

[6] “Cinco Razones Por Las Que La Corrupción No Para De Crecer.” Semana.com, n.d. http://www.semana.com/nacion/cinco-razones-corrupcion-no-para-crecer/160318-3.aspx.

[7] “Cinco Razones Por Las Que La Corrupción No Para De Crecer.” Semana.com, n.d. http://www.semana.com/nacion/cinco-razones-corrupcion-no-para-crecer/160318-3.aspx.

[8] “Governance & Anti-Corruption > WGI 1996-2011 Interactive > All Indicators > Country Selection”, n.d. http://info.worldbank.org/governance/wgi/sc_country.asp.

[9] “Plans to Curb Corruption in Colombian Education System – Colombia News | Colombia Reports.” Colombia News | Colombia Reports, n.d. http://colombiareports.com/colombia-news/news/22829-plans-to-curb-corruption-in-colombian-education-system-.html.

[10] Kimball, Jack, and Bocanegra, Nelson. “Corruption Scandal Rocks Colombia’s Tax Agency.” Reuters News, July 14, 2011.

[11] “Former Rebel Wins in Bogota Mayor’s Election.” Yahoo! Finance, n.d. http://finance.yahoo.com/news/former-rebel-wins-bogota-mayors-163213545.html.

[12] Vaca Vaca, Patricia, María del Pilar Sepúlveda Calderón, and Germán Fracica Naranjo. “Acción del empresario bogotano: creencias y prácticas. Bogotano entrepreneur’s action:” Revista científica Pensamiento y Gestión 0, no. 28 (November 10, 2010). http://rcientificas.uninorte.edu.co/index.php/pensamiento/article/view/981, p. 2.

[13] Ibid, p. 16. Our Translation of the original quote: “considero que el mayor problema que he tenido ha sido mi lucha contra la corrupción y la falta de ética.”

[14] Ibid, p. 16. Our Translation of the original quote: “toca aprender a convivir y manejar estos temas para ser exitoso.”

[15] Guerrero, Manuel. “Esquemas Mentales Erróneos De La Corrupción: Como Estamos Pensandola?” Hojas Universitarias: Revista De La Universidad Central, August 2005.

[16] Vaca Vaca, Patricia, María del Pilar Sepúlveda Calderón, and Germán Fracica Naranjo, p. 13, 15.

[17] Gasse, Y., and M. Tremblay. “Entrepreneurial Beliefs and Intentions: A Cross-Cultural Study of University Students in Seven Countries. ” International Journal of Business 16.4 (2011): 303-314. ABI/INFORM Global, ProQuest. Web. 17 Apr. 2012.

[18] Acs, Zoltan, and Szerb, Laszlo, p. 119.

[19] Ibid, p. 12.

[20] Azcarate, C. “Why Did the Colombia Peace Process Fail?” OJPCR: The Online Journal of Peace and Conflict Resolution 5, no. 1 (2003): 57–65.

[21] The Hidden Crisis: Armed Conflict and Education. EFA Global Monitoring Report. Paris, France: United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, UNESCO, 2011. http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0019/001907/190743e.pdf, p. 216.

[22] Arias, Adriana C. Silva, Juan C. Guataquí Roa, and Patricia González Román. “The Effect of Internal Migration on the Colombian Labor Market.” Global Journal of Business Research (GJBR) 1, no. 1 (January 2007): 80.

[23] “In Flailing Economy, Necessity Entrepreneurship Rising.” Wcfcourier.com, n.d. http://wcfcourier.com/business/columns/in-flailing-economy-necessity-entrepreneurship-rising/article_c5cc4190-24ee-11e1-83f4-001871e3ce6c.html.